installation week

the beginning

This is the first week of my involvement with Floating Land Festival! This week is install week, and while I don’t have any physical elements of my work to install I am dedicating the week to final experimentation and system design for my performance installation series - ‘Hearing Now’. This series of five site responsive performance installations will form the bulk of my data generation for my Masters project of the same name. Data gathering methods will include this journal, field notes, audiovisual documentation, and qualitative data gathered from audiences through a phone-based survey. The design of these performance installations has been informed by Leah Barclay’s ‘Sonic Ecologies Framework’ and my conceptual basis has been explored in my paper ‘Decorating Acoustic Ecology’, which positions ‘decorating’ as a methodological approach to performing with the natural environment that emphasizes attentive responses to ecology and a treatment of my own sound as well as environmental sound as equal parts of the performance. Inspired by Barclay, Vanessa Tomlinson and Lauren Hayes, I am striving to 1) Reveal hidden environmental sound 2) Amplify ecological processes and 3) Decorate acoustic ecology with a view to connect audiences to place through sound.

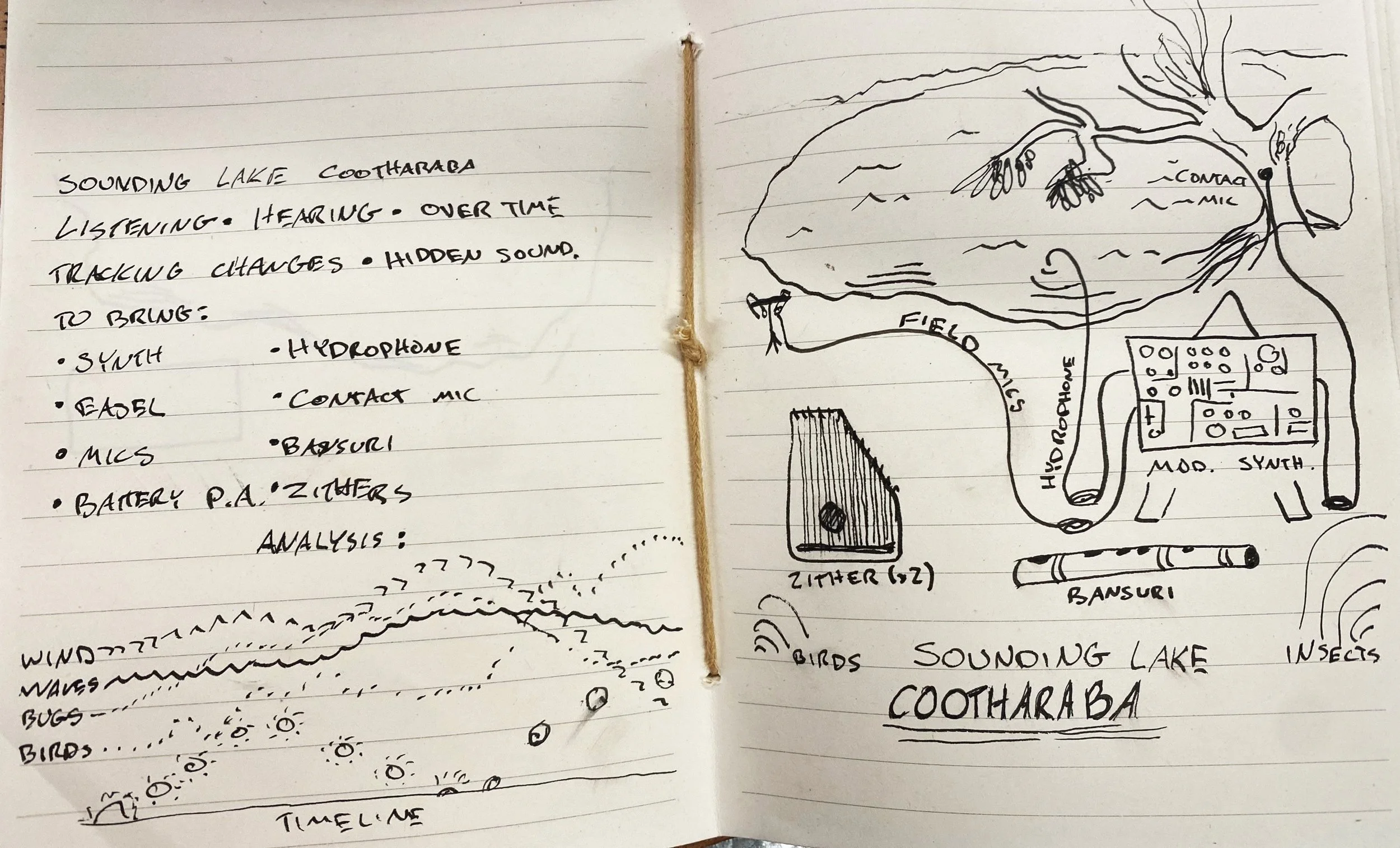

A mock-up diagram of my performance installation for the Floating Land online program.

Amplify ecological processes

To amplify ecological processes (maybe I should use the term audify…) I am exploring how environmental sensing technology might be repurposed to control my modular synthesizer, and thus make audible parts of the environment that are normally inaudible. This essentially built on techniques that I devised in my Honours project to transform human movement into experimental movement through motion tracking and machine learning. In this project however, I am investigating ecological characteristics like wind, light, temperature, and cardinal location as potential data sources to convert into sonic elements.

This week, I identified the Micro:bit microcomputer as a potential tool to achieve this, as I have used this product in the past to detect wind to control digital systems in a computer. The product also has on board compass, temperature, and light sensors. Some brief research suggested that the latest version of this hardware can output MIDI over USB, which would fit well into my current hardware synthesizer setup. I have ordered this new version - if this works, it will be great, as it will eliminate the need for a computer on site to process and convert environmental data.

While this kind of transformation from environment into sound through data is alluring, my previous work in this area has suggested some more nuance. When data sensing is highly specific, or it senses phenomena that are invisible, slow moving, or otherwise difficult for audiences to notice and/or correlate with changes in the sonic output, the impression made on audiences has not been as deep as I might have hoped. Instead, I have often found that tangible data sources, or rich data sources (such as sound) that are more immediately apparent can be more effective at communicating the real-time nature or interconnectedness of the music system.

Hence, while I am exploring environmental data sensing in part, a more significant element of this system is to:

Reveal environmental sound

Leah Barclay and Toby Gifford’s work has been wonderfully defined by the magic of revealing underwater soundscapes to listeners, and much of their research in this area has highlighted the impact that this can have on listeners in terms of passing tacit understandings of ecology on to listeners, or even fostering empathetic connection. During my residency with Floating Land last year, I experimented with attaching contact mics to waterside paperbark trees, and was wonderfully inspired by the dynamic sound worlds that this technique revealed. As described in some depth in my paper ‘Decorating Acoustic Ecology’, this technique picked up the sounds of the lake interactive with tree root systems, as well as a unique resonance in the wood itself. This resonance also lent itself to performance, as manual interactions with the trees could yield a wide range of percussive sounds.

In preparation for the performance at the gallery, I experimented with this technique on waterside plants there - they weren’t paperbarks, but a smaller, more weed-like plant, I will have to find the name. Long branches wove over one another, arching above mangroves at the water’s edge, and then fell into the river. The interwoven nature of these branches created a wide range of interesting resonant impact sounds, close and distant, as they scraped and hit one another. Their presence in the river also allowed the sounds of water to travel through the wood fibre. One interesting new phenomenon I encountered was the sensitivity of the plant/mic system to my voice - perhaps due again to the interwoven nature of the plant, when I amplified the mic significantly, environmental sounds like birds and boats were audible, and my voice even more so. I experimented with singing, sitting in this small, weedy grove, and listening to my voice resonating in my arborous surroundings. Having worked with mostly singular, or isolated, or tall and sparse plant groupings (generally paperbark) this kind of close-knit growth and its immersive potential was something new. I was immediately curious as to how spatialized contact mics might work mixed in a multi-speaker array to recreate space within a tree. Vocally, this is an interesting technique that might reveal some new processes down the line - especially as a recording technique - or, as a live experience, it felt quite meaningful to hear how sensitive plant matter is to sound waves, particularly that of my voice, and hearing my own voice underneath layers of wood sounds went quite a way to inspiring a sense of interconnectedness between myself and the natural world.